There are many books where the narrative is propelled by food. Think Lara Williams’s Supper Club, in which a group of women act upon the idea of taking up more space, literally and figuratively; Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart, where banchan, chamoe melon, and danmuji silently witness the author-narrator’s grief over the loss of her mother; and Nora Ephron’s Heartburn (her “thinly disguised novel”), in which, while dealing with her husband’s affair, the narrator instructs, “Take 6 cups defrosted lima beans…” as if to say “there’s that, and there’s this”. On TV, too, food and drama are made for each other. (Wouldn't you agree, given the success of The Bear?)

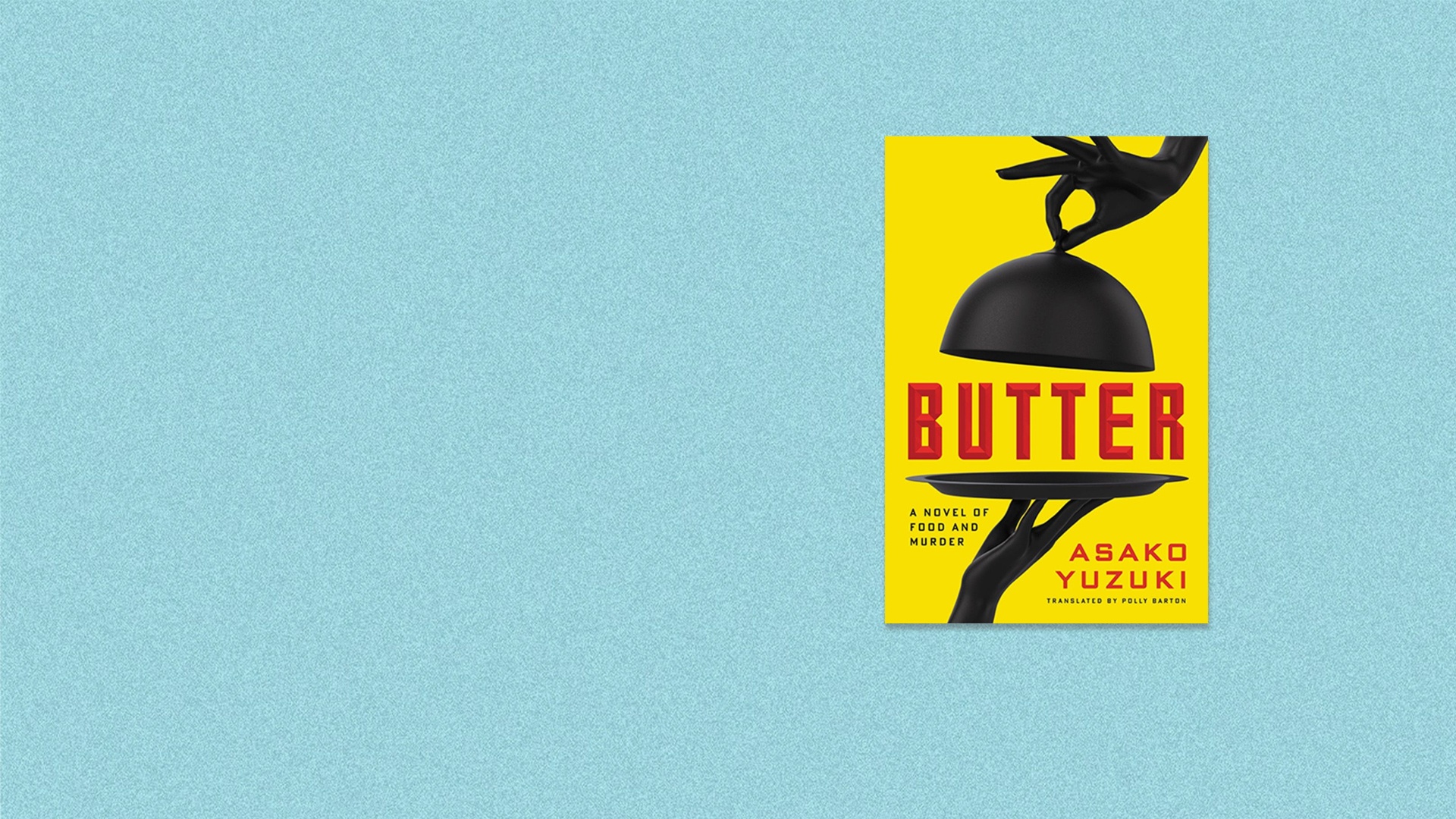

Asako Yuzuki’s latest novel Butter, originally published in Japanese and recently translated into English, is loosely based on the true story of a woman dubbed the “Konkatsu Killer” (marriage-hunting killer), who was charged with killing three men by carbon monoxide poisoning back in 2009.

In Butter, Manako Kajii—or Kajimana—is convicted of killing three men whom she had encountered on an online dating site. There’s no concrete evidence linking her to their deaths (one ODing on sleeping pills, one drowning Jim Morrison-style in a bathtub, one falling in front of a train), but she’s the one person who has cooked elaborate meals for these men.

Recipe for success

Rika, a Tokyo-based journalist, is fascinated, not so much by the murders as by the response Kajii provokes among the public. Kajii is “neither young nor beautiful” and weighs “over 70 kilos”; people's interest and disgust centres on some version of “how could she make all these men fall in love with her?”. Baiting Kajii with a request for her beef stew recipe, Rika manages to get an interview with her at a detention centre. Their subsequent interactions set off a series of events that sweep up Rika and everyone in her orbit.

In Kajii, Rika sees a woman who is unafraid to live life on her own terms, challenging societal conventions of what’s beautiful or feminine as she casually makes pronouncements like: “There are two things I simply cannot tolerate: feminists and margarine”, and who views herself alternately as a modern-day Madame de Pompadour and Breakfast at Tiffany’s Holly Golightly.

Through the story of one woman’s unabashed love of good food and another’s evolving relationship with it, Butter churns a tale exploring themes of fatphobia and body-shaming, misogyny, bullying, sexism at the workplace, female guilt, and ever-elusive redemption.

Food for thought

The novel also interrogates the act of cooking. Why do we cook? Who do we cook for? How do we see the people who cook for us? What is the meaning of the effort one puts into cooking? What happens when someone withdraws, or refrains, from this effort? Is there something dangerous in the meaning we attach to it?

The ‘butter’ of the title makes itself felt in tangible and symbolic ways. There are frequent references to The Story of Little Babaji, a children’s book about greedy tigers who steal Babaji’s clothes and finery and turn into yellow butter, slathered on hotcakes and eaten by Babaji’s family.

When Kajii tells Rika to make herself a bowl of rice and have it with soy sauce and butter, she describes the sensation of eating it as a freefall: “The same feeling as when the lift plunges towards the ground floor. The body plummets, starting from the very tip of the tongue.” This precedes a long paragraph detailing the temperature difference between the rice and the butter needed for maximum impact. In butter, there’s luxury—and a warning.

Descriptions of food are plenty: there’s an entire chapter dedicated to tackling a turkey, along with mentions of an indulgent pollock roe and pasta dish (“there was a rosy-cheeked frankness about the pink of the roe”), a generous buttercream cake akin to “a fall that never ends”, the “clinging, pervasive flavour” of grilled foie gras and persimmons, and the warmth of rice on a cold night in Niigata.

Butter not only makes you think about food—about switching on the rice cooker to make exactly one bowl of rice—but also offers a trenchant critique of a society loaded with impossible beauty standards.