Siddhartha Khosla probably wouldn’t be here today if it hadn’t been for cassette tapes. “I was born in the US, but my parents sent me back to Delhi to live with my grandparents early on for a few years as they set up their life,” Khosla recalls. “They’d send me cassette tapes with lullabies and notes. Even when I moved back to the US, I remember my mother recording her voice on tapes—songs by Lata Mangeshkar, Geeta Dutt, Bollywood duets. I never knew why she did it, but that was my first exposure to music—watching her record and listen to herself.”

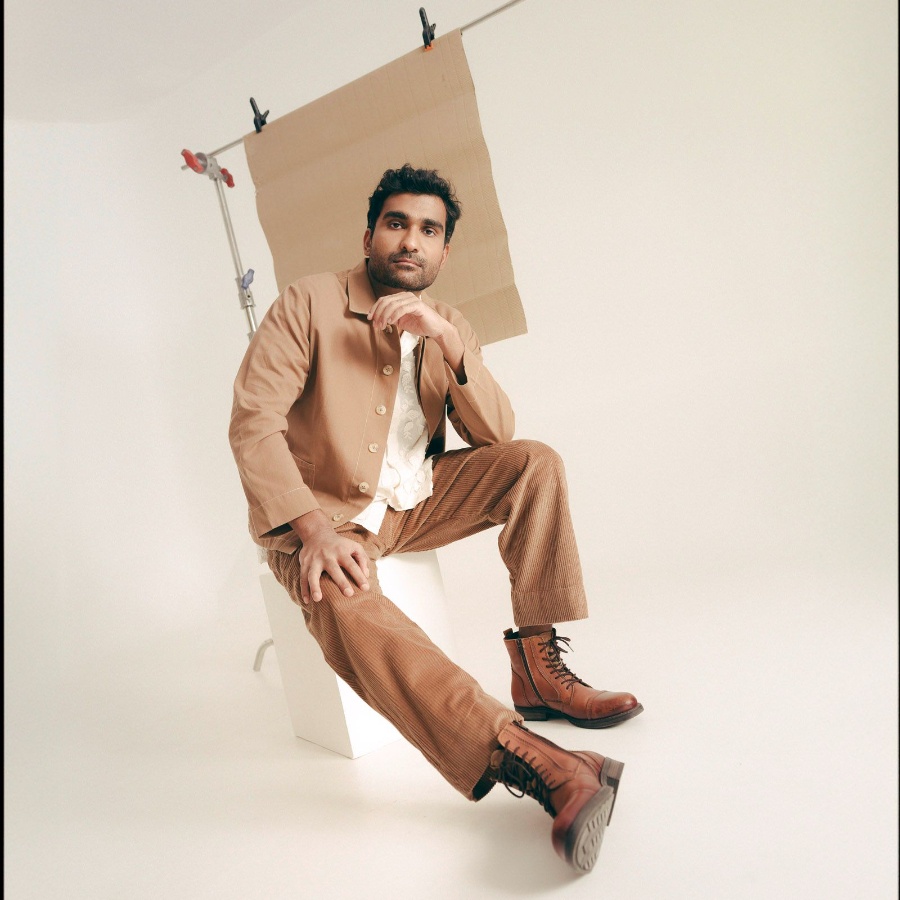

It’s an early August morning, a few weeks before the New Jersey-born, Indian-origin music composer wins his first Emmy, for the score of the superhit series Only Murders in the Building. Seventh time, it turns out, is the charm. “I feel incredibly lucky already,” says Khosla. “You don’t do the work with any expectation of any sort of accolades. When it does happen, it feels good, it feels like your peers are listening.”

A decade ago, Khosla was beloved as the frontman of the indie band Goldspot. Currently, he’s in the most fertile period of his career, composing for the screen, which he’s been doing since the 2010s, but only got his due once the world realised that his music had something to do with the buckets of tears they’d shed watching NBC’s This Is Us. Besides the winning tune of Only Murders, romantic dramas such as The Idea of You and The Family Affair have also benefited from his music.

If you’ve wondered how Khosla conjures that analogue, old-world, oddly comforting quality in his music—first detected in Goldspot’s ‘Friday’ and now in the score for This Is Us—consider the instruments and tools that have populated his life. Along with cassette tapes, Khosla remembers owning a boombox, a recorder-cum-radio device. Through the tapes, he tapped into Indian music (learning the lyrics to Anup Jalota songs would be his homework); and toggling the lever to radio introduced him to global acts like REM, The Beatles, The Cure, The Smiths, and more.

Let’s rewind

In the 1990s, Khosla was the dorky eighth-grader who got up on stage in front of the whole school dressed in a kurta pyjama to perform an Anup Jalota song on the harmonium for cultural diversity week. That was when his friend Sanjay approached him and asked him to join a new band. “So we were the Hip Hop Hindus,” Khosla laughs. “We did covers of Nine Inch Nails, we did Black Sheep and US3, The Cure, Red Hot Chilli Peppers, Pearl Jam…it was the best of times.”

The Hip Hop Hindus didn’t go beyond school, but even as they took their L-SATs and tried to figure what would come next, they knew they weren’t finished with music yet. Almost on a lark, Khosla moved to London with his then bandmate—living in a one-bedroom apartment, working as bartenders, and recording their songs on a Tascam 4 recorder. The dream ended when they got fired and were told their demos were “shite”.

Six months later, with their visas expired, they moved to LA, where a friend of Khosla’s from college, who owned a recording studio, offered to produce their music. That was where they recorded their first EP as Goldspot. But, of course, life happened and Sanjay left for law school. Khosla, though, wrote ‘Friday’, which became popular enough for him to begin working with other musicians, and that’s when Goldspot really took off.

The band landed a deal with UK-based label Mercury, with whom it released its debut album, Tally of the Yes Men. “That was my introduction to the world of major labels. We were the sort of the band that the A&R people really loved, but we realised it would be tough to break into the mainstream. Our music had an artful quality to it, it wasn’t straight-up pop in any way, it had these old Indian influences. It was its own unique, specific thing.”

Despite the great press, the album didn’t do well in sales—perhaps because this was when everyone had begun to get their music as MP3s on iTunes. Concept albums became elusive, the single emerged—and Goldspot lost its record deal. Khosla made the next two albums, And the Elephant Is Dancing and Aerogramme, independently. But he did get to tour India (at one of the early Weekenders), a highlight of his life. “The dream was that it would continue,” he says, a slight note of sadness in his voice. “My dream was to have a really successful, big band. But the truth is that your career is not linear. The only thing that [can be] linear is your commitment, not the path.”

Keep on humming

Lately, Khosla has been humming more than he has been singing. The hum in the Only Murders title score is arguably what makes it such an earworm, a joyful, suspenseful, dramatic thing, in which plastic buckets for percussion sit at total, unexpected ease with orchestral violins and lo-fi textures from a digital Mellotron. “The Only Murders theme could be a melody from an old Raj Kapoor film,” Khosla laughs. “To most people, it doesn’t sound like that, but it does to me; probably the minor key of it, and the melancholy of it.” As a music composer, he thinks his job is to be able to capture the essence of the script, story, and characters, while also matching the tone. “This one has been a pretty challenging tone to thread,” he observes. “There’s comedy, drama, mystery, sadness—how do you make music that tells that story, without being straight-ahead comedy music?”