Imagine a world where, whenever you wanted a new chair for your office or lampshade for your bedroom, all you had to do was put together a pile of kitchen waste and watch it grow. Unfortunately, product design is nowhere near that level of elfin magic yet, but mycelium gets us relatively close. At least, that’s what it sounds like when Bhakti V Loonawat and Suyash Sawant, co-founders of Mumbai-based product design studio Anomalia, run through the list of products they have been developing using the thread-like mushroom root system.

So far, the duo has created partition systems for acoustics; a block that can hold 40 times its own weight; and a series of chairs that is part of an ongoing furniture series called MycoLiving, all using their material of choice—mycelium. And up next is a mycelium light fixture. “The light is growing right now,” Loonawat says, immediately inspiring visions of a futuristic wonderland where plants and humans live in symbiotic harmony.

Mycologists like Paul Stamets have long extolled the virtues of mushrooms, and this seems to have caught on in sustainability circles today, with everyone raving about the root system of mushrooms. In other good news, it is a renewable resource, it grows on waste, and it is a viable replacement for PU-based materials like foam and faux leather. An added bonus in a country like India is that large-scale mycelium manufacturing, which requires agricultural waste, could offer farmers an additional source of income and eliminate their dependence on crop burning. Already, the material has made a mark on the design world at large. Last year’s Belgian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was clad in mycelium panels developed by biotech company PermaFungi, and a few months ago, Cadillac announced a collaboration with mycelium-focussed MycoWorks to develop the material for its car interiors. Fashion has responded on cue as well—with Stella McCartney’s Frayme Mylo™️ leading the charge and designing a designer bag made from mycelium. Anomalia, too, is collaborating with fashion designer Anushé Pirani on mycelium leather apparel that will soon be available for retail.

In India, companies such as Roha Biotech and Dharaksha Ecosolutions are spearheading the application of mycelium as a packaging material, while even companies like Dabur, Barosi, and Kraft Packaging are jumping on the bandwagon. And now, architects are investigating its potential as a structural material, in the hope that it could become the very fabric of our built environments.

Will we one day be living in buildings that magically ‘grow’ out of old hay and sawdust? It turns out that’s exactly what Anomalia is hoping to explore through a fellowship with Godrej Design Lab. “We’re building a pavilion out of 300 of our blocks, interlocked and stacked,” explains Sawant. “Till now, people have seen mycelium in its capacity as a cladding material, but not as something that is under compression as a wall or a column system. That is what we are trying to do.”

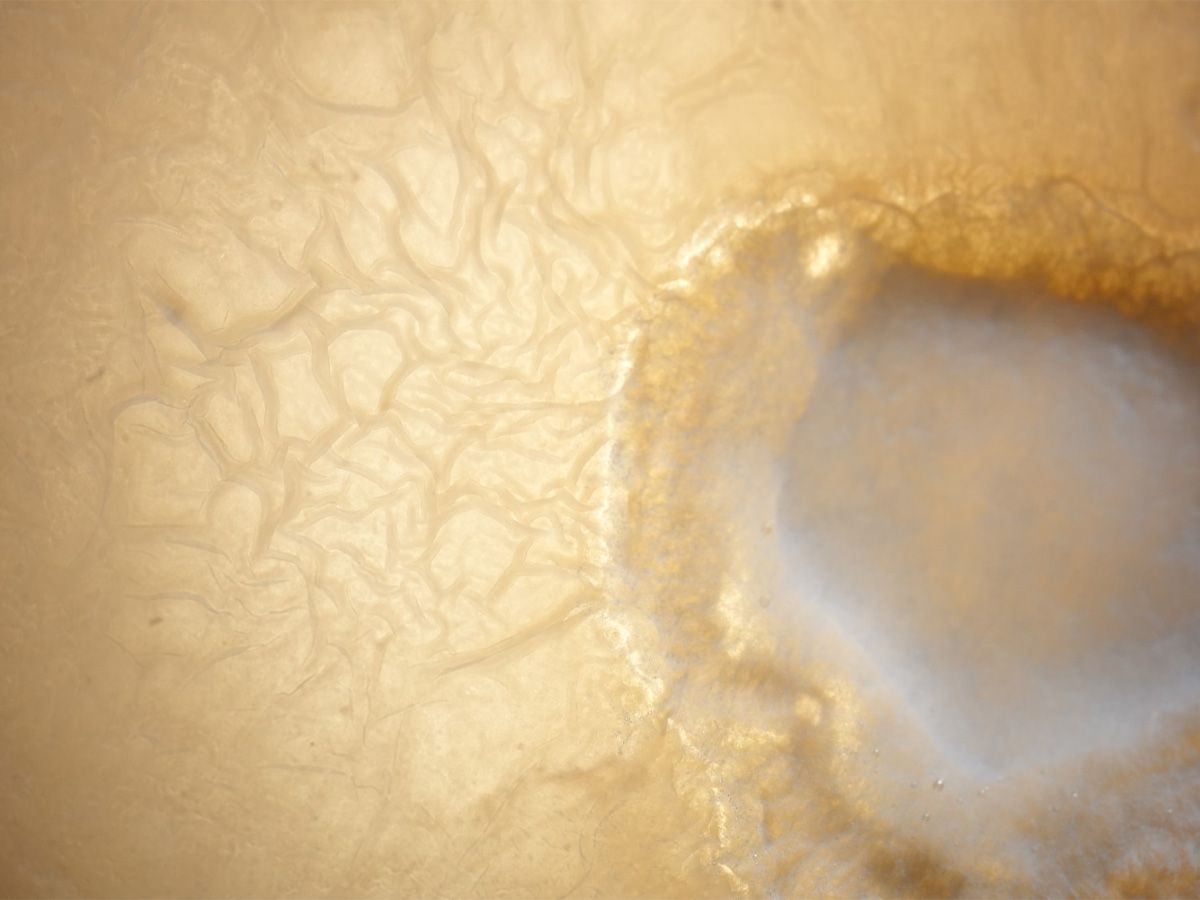

Loonawat and Sawant’s introduction to the material came in Barcelona, when they were pursuing their postgraduate degrees in architecture at the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia. “We were aware of mycelium as a material, but in Europe, we got a sense of how it could be put into practice,” Sawant recalls. The duo started experimenting with it during the lockdown, by growing mycelium in cupcake trays. Given that mycelium grows naturally on waste, it’s fairly low-maintenance, but even a minor bacterial contamination can alter the integrity of the substrate, and, consequently, its viability for architectural use. They now enlist biotech partners like Roha Biotech, and Indonesia’s MYCL Bio to grow mycelium for them in climate-controlled labs—in return, Anomalia’s design explorations offer these companies an opportunity to experiment with and develop new substrates that could revolutionise architecture.